Strengthening trauma-informed care and services for survivors

Survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault who make it to SafeHouse Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan, are a step closer to healing and reclaiming their lives, but that doesn’t mean the trauma of their experiences has gone away or that the road ahead will be an easy one.

Reactions to trauma may be boldly present or hiding below a calm surface, just waiting for a trigger. In either case, the toxic stress of trauma can take its toll on survivors’ physical and mental health.

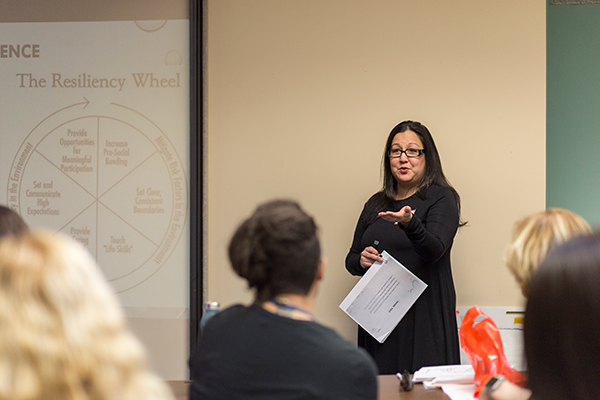

The training

That’s why more than two dozen SafeHouse Center employees gathered for a training session with University of Michigan School of Nursing (UMSN) faculty and staff members who specialize in trauma-informed care. It’s an approach that incorporates recognizing the effects of trauma, then using that knowledge to optimize services. The goal of the training session was to provide SafeHouse Center employees with a deeper understanding of how trauma can impact well-being and how they can use that knowledge to assist survivors.

“We are always looking for opportunities to further support survivors,” said Barbara Niess-May, SafeHouse Center executive director. “We always want to learn more and understand every possible way to be supportive to them.”

“We are always looking for opportunities to further support survivors,” said Barbara Niess-May, SafeHouse Center executive director. “We always want to learn more and understand every possible way to be supportive to them.”

ACEs

One focus of the session was on how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can influence health and behavior, even long after the experiences occurred. Examples of ACEs include violence, neglect, unstable housing, or having an incarcerated parent. It’s not unusual for survivors and their children who are at SafeHouse, or similar facilities, to have a history of ACEs.

“People who have witnessed or experienced adverse experiences are more likely to have risky health behaviors, chronic health concerns, and mental health problems such as depression,” explained UMSN Clinical Assistant Professor Elizabeth Kuzma, DNP, FNP-BC.

Substance misuse, unintended pregnancy, and trouble in school, jobs and relationships are also common outcomes from an adverse childhood experience. In addition, children who experience trauma can have altered brain development, decreased language skills and difficulty forming healthy relationships. The risk and number of consequences can increase when individuals have more than one ACE.

The faculty and staff members who provided the training are part of the UMSN study group CASCAID (Complex ACEs, Complex Aid). The group is focused on understanding how ACEs affect people throughout their lives and how to help people heal emotionally and physically. The work includes research, community education and working with providers to incorporate trauma-informed care into practice.

Changing Approach

“There are ways to help and that’s why we are here,” said UMSN Assistant Professor Yasamin Kusunoki, PhD, MPH. “It’s important that the approach moves from ‘What’s wrong with you?’ to ‘What happened to you?’ As service providers, there are four key things we can do to provide trauma-informed care. The first is just realizing the impact that trauma has beyond that initial situation. The others are recognizing the signs of trauma, responding appropriately and resisting re-traumatization.”

Re-traumatization was a particular area of concern, as one SafeHouse Center employee explained.

“When someone calls for help, I have to ask them questions about what happened so I can get them connected to the appropriate services,” she said. “And I feel terrible that I’m making them explain this awful thing that they’ve been through.”

"When somebody is re-traumatized, alarm reactions go off for them, as though the original trauma is happening again,” said UMSN Assistant Professor Laura Gultekin, PhD, FNP-BC.

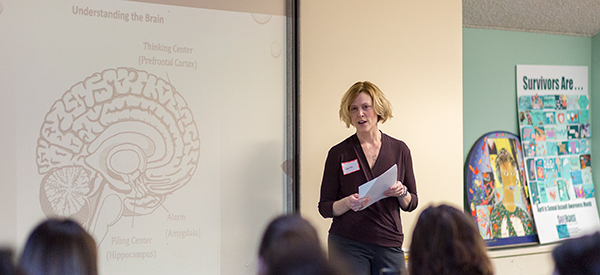

Brain science

Gultekin spoke with employees about some of the brain science behind potential behaviors. She explained that sometimes rules or actions that are well-intentioned, are recognized by survivors as threatening, causing an alarm response from a person that may seem extreme.

Gultekin spoke with employees about some of the brain science behind potential behaviors. She explained that sometimes rules or actions that are well-intentioned, are recognized by survivors as threatening, causing an alarm response from a person that may seem extreme.

“Certain things can seem harmless, but it could be a trigger for them,” she explained. “For example, a homeless shelter I work with has rules about where residents are allowed to keep food to prevent issues with pests. Some clients have a history of not knowing where their next meal is coming from so restricting what they can do with their food can be upsetting.”

Gultekin explained that when an alarm goes off, it sends the person into a heightened state of distress. It can activate a “flight or fight” response that makes it hard for the person to focus on anything else. These alarms are protective, and in many cases, people can assess the alarm, recognize that the stress is not truly threatening, and turn it down or off. However, for individuals who have been exposed to recurrent or extreme stress, they may have difficulty distinguishing real threats from false ones.

“Flushing, clenching a fist, those are all signs that a person is reacting to an alarm,” said Gultekin. “It can also go the other way where the person shuts down. When that happens, you want to use strategies to de-escalate. It can be as simple as saying, ‘I see you’re getting upset, let’s walk away for a few minutes.’ You have rules for a reason, but you can start a conversation and see if there is a way to help that person feel better.”

“Flushing, clenching a fist, those are all signs that a person is reacting to an alarm,” said Gultekin. “It can also go the other way where the person shuts down. When that happens, you want to use strategies to de-escalate. It can be as simple as saying, ‘I see you’re getting upset, let’s walk away for a few minutes.’ You have rules for a reason, but you can start a conversation and see if there is a way to help that person feel better.”

Moving forward

“I think the training provided the staff with language for a lot of concepts they work with currently but may not have had the verbiage to describe in the past,” said Lindsay Cannon, a UMSN clinical research coordinator. “I think a lot of staff were also challenged to think critically about their current practices, as exemplified by the constructive discussions that took place surrounding cases that could have gone better. Many staff members expressed that this was a good jumping off point that ignited their fire to learn more about trauma-informed care and interventions for trauma.”