Community research to reshape health care for young Black men in Detroit

Written by: Alex Bienkowski

Over the last year, Assistant Professor Jade Burns, Ph.D., RN, CPNP-PC, has been leading community-centered research in Detroit as part of a dynamic project to improve health education, access and outcomes for young Black men in urban communities.

Before COVID-19, her project, Young Men’s Health Matters, relied on in-person interaction to gain a deeper understanding of the community’s most pressing health care concerns. But in light of social distancing guidelines, Burns has drawn on her expertise at the intersection of technology and health care to adapt her approach. Those efforts, combined with a heightened awareness of health disparities and racial injustice, have broadened the scope of her work, creating new opportunities for a comprehensive conversation on Black men’s health.

Burns has worked with Detroit’s youth for more than 15 years in a variety of clinical, community-based and academic capacities. Her research focuses on using technology and digital spaces to improve access to health care services for adolescents and young adults, specifically young Black men and other youth of color, with an enhanced focus on sexual health.

Last year, Burns received grants from the Detroit Urban Research Center and the Institute for Research on Women and Gender for the Young Men’s Health Matters project. Through the establishment of a powerful community–academic partnership, the project aims to improve the well-being of young Black men by identifying barriers and facilitators to their health care.

Burns and her DRB Lab partnered with Detroit Community Health Connection, Inc. (DCHC), a federally qualified health center that provides primary care services through seven different locations throughout Detroit. Burns, who used to work as a DCHC health care provider, remembers an earlier promise to return to the center and serve the community with a new mission.

“I told them, ‘When I get my Ph.D., I’m going to come back to you, and we’re going to work together,’” she recalled. “I’ve served this community as a clinician, and now it’s time to create research that includes the community so they can benefit. I’m very passionate about that.”

Social justice through health equity

“The ultimate goal of my work is to utilize community-engaged research and technology to increase access to health and health care,” Burns said. “But it’s hard to get into the community; it sometimes takes years to build relationships and trust.”

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) defines Burns’ approach to her work. It is a collaborative framework that involves community members, organizational representatives and academic researchers in all aspects of the research process.

“It’s about connecting with the community, building partnerships, listening, gathering data and using it to tailor solutions that are representative of that population,” she explained.

In the fight against systemic racism, which has been amplified in recent months by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless others at the hands of law enforcement, Burns sees CBPR and health research as important tools for social justice.

“Social justice must include health care,” Burns said. "The effects of systemic racism in health care have long been acknowledged. Is injustice in health care any different than the injustice in any other system?

“If Black lives matter, so must the health of young Black men. The numbers are staggering and very clear. The health inequities are clear. With so many Americans of all backgrounds asserting the value and basic right to life of Black and Brown people, we must address these gaps and affirm that these lives matter in our health care system. My research aims to do just that.”

Facilitating community conversations

After conducting a needs assessment, Burns and DCHC brought together an advisory board of community leaders to discuss the most effective ways to engage citizens in thoughtful conversations about their health. Burns wanted to examine how creating a local men’s community forum could create awareness of health disparities and improve unity in an urban setting.

“A lot of people hold health fairs and other events, but who is measuring those things, and how do we know if it works?” Burns asked. “Those events are important, but what does it mean afterwards? We need to figure out how to measure it.”

Burns and her partners developed a series of three community health forums on Detroit’s east and west side, bringing together local residents and various community organizations focused on issues like employment, food security and mentorship.

Burns began each forum by outlining her ambition: “I want to know what you think about what’s going on in your community, and I’m going to help build science to create sustainable programs there.”

The conversations that took place quickly exceeded her expectations.

“It turned into this therapeutic session, and we found out that a lot of health behaviors intersect when it comes to young men’s health,” she said. “It was so beautiful to see how honest they were. They really opened up and started speaking candidly about pressing issues.”

Many of those issues included socioeconomic factors such as job opportunities and financial literacy, as well as behavioral health concerns, sexual health education, mentorship and violence.

A pandemic provides a different platform

A pandemic provides a different platform

At the start of the year, plans were underway for a major conference in Detroit that could build broader engagement around the issues addressed in the community forums. Then COVID-19 brought everything to a standstill.

“We just figured we wouldn’t be able to do it,” Burns admitted. “Then we said, ‘Wait. Let’s do it, make it virtual and hold it during Men’s Health Month.”

In June, the U-M School of Nursing, DCHC and the Curtis Center for Health Equity Research and Training at the U-M School of Social Work teamed up to host two virtual events focused on Black men’s health.

The Black Men’s Health Summit took place June 6. An engaging panel of speakers included Michigan Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist II detailing the state’s COVID-19 response efforts and the development of the Michigan Racial and Health Disparities Task Force. Detroit Police Chief James Craig shared his perspective on protests against police brutality and the larger impact of violence on men’s health. Other speakers covered topics including access to mental health services and the stigmas that prevent Black men from seeking support, as well as barriers to STEM education in Black communities and the risk behaviors that contribute to adverse health outcomes for Black males.

“This summit may have provided a safe space to promote social action, and I think it provided essential resources during a time when this community needed it most,” Burns said. “Not everyone may have had the opportunity to participate in a peaceful protest. This was a way to ‘do something’ by promoting wellness and activism.”

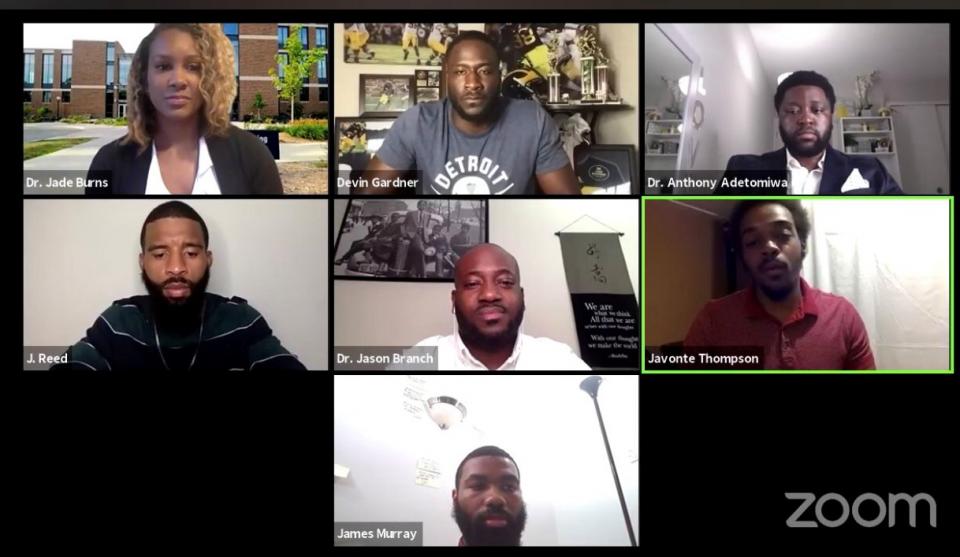

The second event on June 23 shifted the focus to a younger audience in a more conversational format. Real Talk: A Dialogue on Health, Wellness and Success for Young Black Men brought together a physician, counselor, community activist, professional musician and even a former Michigan quarterback to share valuable perspectives with parents and young adults in a digital space. The panel of current and former Detroiters tackled a wide range of topics, including mental and emotional health, how to address issues of systemic racism, the importance of the arts, health disparities and much more. The panel also took questions from attendees throughout the hourlong webinar.

“I think through both of these events we gave men an outlet to not only talk about health, but also many of the important issues going on within this country and our state,” Burns said.

Measuring data to effect change

For Burns and her research team, both events presented a valuable opportunity to collect and analyze data that can lead to tangible benefits for urban communities.

Attendees at The Black Men’s Health Summit were 80% male with an average age of 37. Nearly half of audience members were from the Detroit metro area, but many others came from cities across the country, including San Diego and Washington D.C., representing an array of professions.

A poll conducted during the event revealed:

- At a minimum, 40% of participants polled felt "very" stressed during this pandemic.

- Growing up, 51.2% said they did not engage in STEM activities.

- 61.8% said they were extremely knowledgeable about safe sex practices.

- 38% said were moderately aware of mental health services.

Burns is now focusing on how information obtained during the community forums and two virtual events can guide the next phase of her research. The group recently released a survey to continue their analysis of Black men's health and health care preferences in order to optimize health care services for Black men across the age spectrum in urban settings.

“The survey gave me an opportunity to not only ask about the most pressing health issues, including COVID-19, but also dive deeper into questions about violence and its impact because of all that has happened in the wake of George Floyd’s death,” Burns explained.

She will use the survey results to take a closer look at what Black communities need, specifically the priority health care needs of Black men in Detroit, segmenting the information along generational lines. While her research focuses on the Detroit community, Burns hopes the data she’s collecting will carry valuable implications beyond the boundaries of the Motor City.

“We hope to build a registry of cities across the country that looks at cross-sectional data for health preferences, resources and access to care for Black men across the age spectrum,” she said.

In the weeks and months ahead, Burns will continue to work with DCHC and the advisory board of community leaders to keep the focus on the population she has been invested in throughout her career.

“I will continue working with our group to focus on adolescent and young adult males,” she said. “I’m very passionate about them, especially youth of color, so I’m going to continue to fight that fight and make sure science is always part of the conversation surrounding that population.”

The future of nursing depends on world-class education and research. In this uncertain time, you can provide critical support to the U-M School of Nursing by making a gift to support important diversity, equity and inclusion efforts.