Faculty impact: Caring for children with cancer paired with evidence-based practice to help parents

A health scare as a teenager turned into lifelong inspiration for Elizabeth “Beth” Duffy, DNP, RN, CPNP, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Michigan School of Nursing (UMSN). She had abnormal blood cell counts and there was concern she might have leukemia.

“I didn’t have cancer, but it really opened my eyes to what I wanted as a career,” said Duffy. “I had the opportunity to see pediatric nurses working with this fragile population and they were extraordinary. I was already sure I wanted to work with children but that’s when I knew I wanted to be a nurse.”

Duffy remained healthy and she committed herself to helping children who are not as fortunate. After earning her BSN from UMSN, she immediately went to work in pediatric oncology at U-M’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital.

Duffy remained healthy and she committed herself to helping children who are not as fortunate. After earning her BSN from UMSN, she immediately went to work in pediatric oncology at U-M’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital.

“Working with children is exceptional,” said Duffy. “They are hopeful, resilient and so wise. I’ve learned so much about life through them.”

Evidence-based practice to help parents

A significant aspect of caring for children with cancer includes helping the parents navigate the daunting diagnosis and treatment.

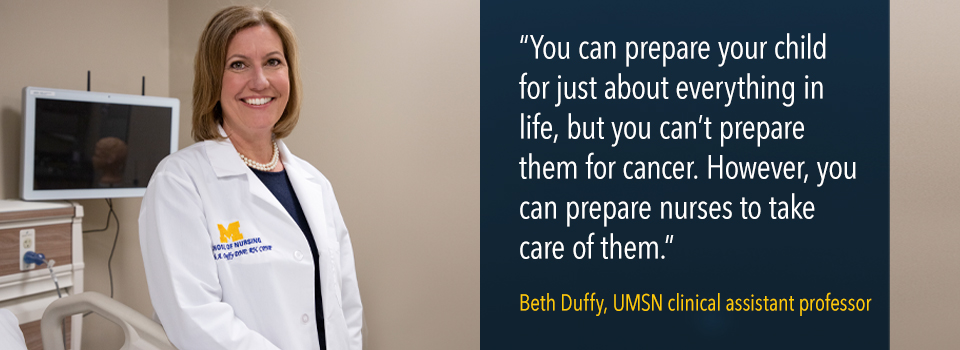

“It’s a helpless feeling for these parents,” explained Duffy. “You can prepare your child for just about everything in life, but you can’t prepare them for cancer. However, you can prepare nurses to take of them.”

Duffy is applying her years of experience and education to advance nursing practice in several ways. She was recently appointed to be the chair of evidence-based practice for Children’s Oncology Group. In addition, she’s leading a new project to help parents manage the overload of information that comes with a child’s cancer diagnosis.

“It’s a really emotional time and we have parents say, ‘I don’t really remember what you told me earlier,’” said Duffy. “It’s overwhelming because they know there is so much information they need to learn quickly, but they don’t know it yet.”

The new strategy breaks down what parents need to know by when they need to know it.

“Right now they get two big binders, a PowerPoint show and hours of education,” she said. “It can be too much. This approach is focused on the emerging things you have to know to take your child home. Once you get through that, then we’ll have time to get you through the other parts. It’s primary topics, then secondary topics and tertiary topics, instead of all in one big bucket.”

Nurses leading care

Duffy believes this is a logical area for nurses to lead because of the amount of time they spend with the families.

“You can meet the parents where they are and individualize it,” she explained. “We can see when they’re ready to learn more and when they are just too tired or stressed to take anything in.”

“You can meet the parents where they are and individualize it,” she explained. “We can see when they’re ready to learn more and when they are just too tired or stressed to take anything in.”

Duffy is also focused on evidence-based scholarly work to prevent a common, but sometimes devastating complication - central line-associated bloodstream infections. A central line is a catheter that is inserted for long-term therapy, which is very common in oncology, and it can stay in for years.

“The infection can be fatal,” said Duffy. “That’s the worst case, but there are other concerns. It delays chemotherapy and it can be very costly.”

Duffy says preventing infections can be difficult when parents are trying to keep a semblance of normalcy for the child or trying to prevent them from more pain. For example, a child may feel well enough to play outside which can expose the central line to different germs.

“As nurses, we can use evidence-based practice to empower parents to care for that line through whatever the child is doing or however they are feeling,” said Duffy. “That work is truly nursing.”

Teaching students

Pediatric oncology is often as viewed as one of the most difficult clinical rotations for nursing students because of the physical and emotional toll.

“Some of the patients that are there on the student’s first day are still there when they leave,” said Duffy. “They don’t know how the story ends for that patient. It really becomes challenging.”

It can also be difficult for students to see children pass away.

“It can be really hard to balance because they may have an emotional day at the hospital and then they go back to collegiate life,” said Duffy. “It’s a tough clinical.”

However, these cases can be some of the most valuable learning experiences.

“The students love getting to know the families,” said Duffy. “There isn’t an automatic trust from parents because they know they are students and they’re learning. But by the end of the semester, they view them as nurses. It’s such a positive experience.”

Duffy says she’s continually inspired by UMSN students.

“They are dedicated to not only being academically and clinically ready, but they are driven to be great nurses,” said Duffy. “You can teach them the clinical acumen, but when you see them do the parts of nursing that you can’t necessarily teach, that they do instinctually, as a teacher I don’t think there’s anything better than that.”

And as a nurse, Duffy says it’s the impact and connections that keep her motivated through the difficult times.

And as a nurse, Duffy says it’s the impact and connections that keep her motivated through the difficult times.

“The ability to really help this child through a very difficult situation and then see them grow up and go to their graduation party or their weddings, that’s the special relationship that I like,” she said. “The job is hard, but it’s also really rewarding.”

More

A Reunion 20 Years in the Making: “Thank You for Giving Sweet Baby James a Second Chance in Life” tells the story of Duffy inviting one of her first patients, and his mother, to a class to share their story.